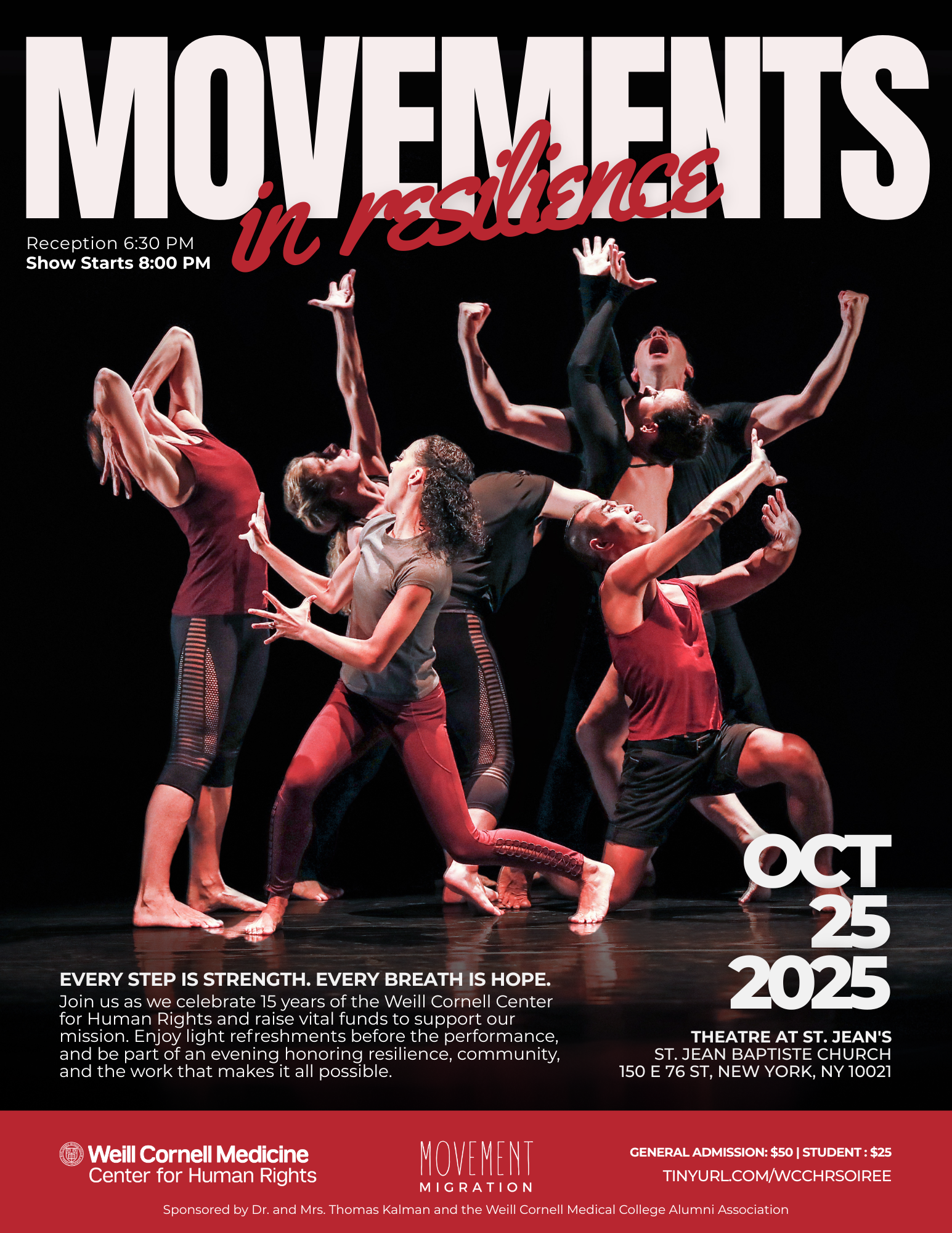

WCCHR Events

WCCHR Pods

WCCHR Pods is a monthly discussion group discussing cases. WCCHR Pods session has ~5 clinician evaluators with ~10-15 students to learn about human rights advocacy, build skills for conducting forensic medical evaluations, and foster mentorship and community. We meet on the first Thursday of the month from 6-7 pm throughout the year. Please email wcchr@med.cornell.edu if you would like to be added to the listserv.

WCCHR Speaker Series

WCCHR Speaker Series are our monthly speaker events. In the past, we have invited speakers to discuss ethics in human rights and reproductive justice.

WCCHR Training

We hold Spring and Fall training sessions, once a semester, to train new evaluators and student volunteers.